John Kavanagh reflects on his experience of fieldwork at the University of Liverpool and the changes that have occurred over the last few years. He also talks about today’s need to make greater use of digital media to help students acquire field skills and how he has helped develop virtual mapping exercises at Liverpool. John’s reflections were sparked by a talk by John Howell (University of Aberdeen) at one of the Earth Science Research Group seminars at Liverpool.

There’s no getting away from the fact that Geology is a subject best viewed in 3D and as we all know the best place to view geology in 3D is out in a field, preferably a warm dry field. So, for time immemorial geologists have been going out to record observations, draw diagrams and visualise what’s happening to the rocks below their feet. But what happens if you cannot go outside? What happens when the next generation of geologists cannot get access to the exposures we once used for training? Well, the last two years have seen not quite a sea change but certainly an acceleration in the use of digital media to help obtain field skills. We have seen geologists and other scientists successfully adapting the technology once only available to national surveys and big companies but now ready to buy off the shelf at Argos.

My first experience of fieldwork at Liverpool was digital. Working under the auspices of John Howell, who’d put together a crack team of sedimentologists and people who were already beginning to think about how to turn the world virtual. The project was to create a reservoir model of Woodside Canyon. Three weeks of logging and Differential GPS-ing of surfaces and some dodgy laser rangefinder data later, the raw data was collected. It took another month of computing time with Statoil for John to come away with his reservoir model.

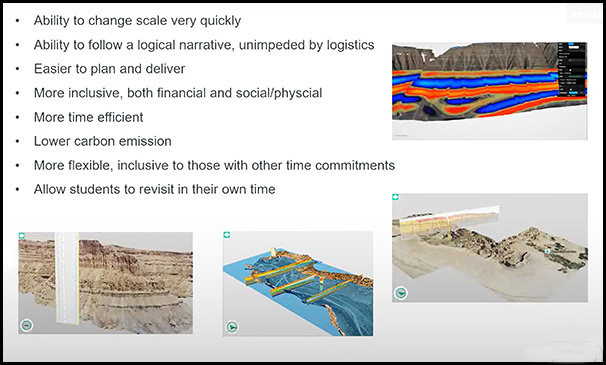

Come forward 20 years, past the revolution that was LIDAR, and John can send up a drone, collect 30 minutes of video and a few hours later can have a digital elevation model of an exposure draped with an orthophoto mosaic, that can be interpreted into a reservoir model. Seismic data, field and wireline logs and even 3D SEM images can all be put in place and viewed and interpreted in augmented reality. Beyond the off the shelf drone there is also twenty years of experience and software development in there as well…. But all of this brings us to a position where we can collaborate with, and train professionals based anywhere in the world on the same exposure at the same time.

So, what of Liverpool’s virtual field classes? I was involved with three field classes, two of which were delivered in an online format, and the final year project which thankfully had a fieldwork component. Our first- and second-year field classes are field skills training modules so it was important that these skills could be developed. I was able to put together a set of exercises using field photographs to help students gain confidence in facies recognition which ultimately fed into a photo-based logging exercise for the cliff at Amroth in Pembrokeshire.

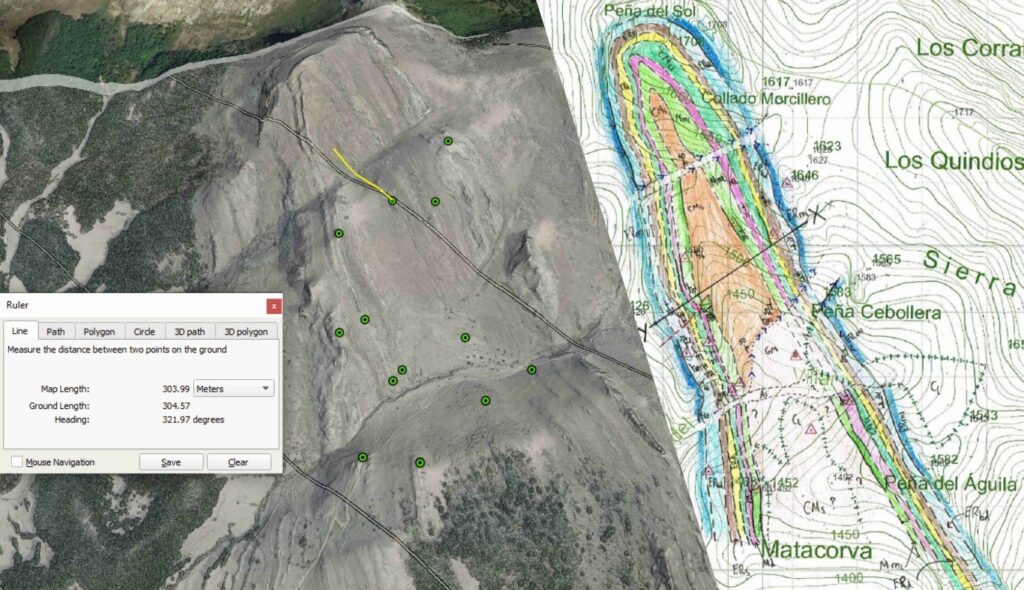

For our second years, a decision had already been made to create a virtual mapping exercise based on an old mapping training area in Cantabria, Spain. Luckily one member of staff had a fairly extensive photographic collection of exposures – what can I say? I knew they might come in handy one day. Spain also has freely available 1m LIDAR datasets. With this we were able to create a slope map which could be overlaid onto Google Earth. A set of location cairns was also placed onto Google Earth as reference points and using the measure tool we could re-create the taking of bearings in the field with a compass. These distance and bearing measurements could then be transferred to a paper map using a compass to locate geological contacts. The contact type and any topographic evidence could then be added to the paper map and the contact followed using the measure tool – essentially, we had re-created the skills needed to recognise topographic evidence for geological contacts, the type of contact and how to trace it out along the ground and add it to the map. Colouring of exposure could be added to the map as they were visible on the imagery and then a set of strike and dip data could be added using grid references. The whole exercise was kicked off with a “recce” day where exposure photographs and field notebook excerpts were used to determine what the rocks were and how they could be split or lumped into the mapped formations. This is as close to an authentic field experience without being in the field or using augmented reality goggles.

The result, a set of field maps and cross sections which were comparable in quality to the maps created in the field by previous cohorts, all be it without the inevitable suntan lotion and grass stains. In fact, the exercise produced some unexpected similarities with the field drawn cross sections. One could argue that the students using Google Earth had an unfair advantage being able to view the fold in the area across its profile plane but the age-old problem of extrapolating straight lines to the centre of the earth still came up!

The virtual logging exercise created similar results. The grain size profiles on the whole probably edged the field-based logs due to the limitation of having to provide that information to the students. However, recognition of sedimentary structures should have probably been better from the photographs due to the bias of taking photos of good examples. There was also the inevitable addition of jointing to the logs, which again happens in the field. On the whole, I suspect that the students would have thought that they would have done a better job in the field, but the same mistakes appeared so it’s probably a better reflection of how comparable the observation and collection of field data was. On the brighter side – one of our honours students was able to use the skills obtained tangentially! Running out of daylight at the exposure he was working on, he took photographs – confident in his ability to be able to interpret sedimentary structures and process and produce a log from them. I literally cannot tell you how happy this made me feel when I heard this but there were goose bumps.

So, in essence you can’t beat a real exposure but life in the virtual world could offer a good way for students to gain confidence in field skills before embarking on the first field exercises. Something that more and more students have anxiety about, as for some it may also be their first time away in the wilds of Southwest Wales anyway.

Click on the image to see a short clip from John Howell’s talk.

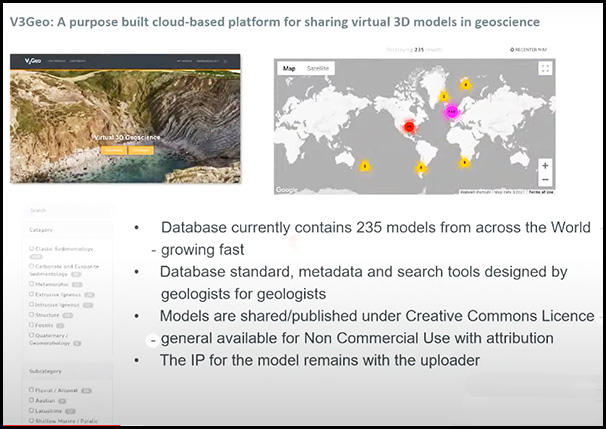

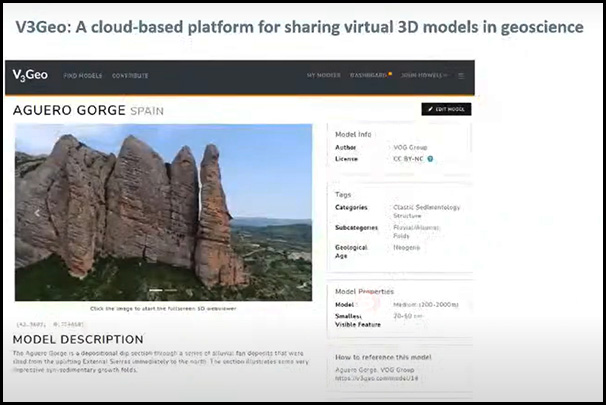

In his talk John Howell explained that there have been several initiatives to facilitate the public sharing of virtual outcrop data via website and online databases. V3Geo.com was launched in April 2020 to provide virtual outcrop data to groups and institutions who were unable to visit the field due to the global lockdown. He also outlined the long-term goal of providing a public resource that captures all the key outcrops in the World and beyond.

Leave a Reply