JESEI

teacher’s notes

student’s notes

Crystal size and cooling rate: fast and slow cooling of lead iodide:

teachers’ notes

Level

This activity is intended for students aged 11-14.

Topic

The activity relates to the process of igneous rock formation by the cooling of magma. It can be used to illustrate how the rate at which

molten rock cools affects the size of the crystals that form within the solid rock – rapid cooling producing small crystals, slower cooling

producing larger ones.

Description

Hot, saturated solutions of lead iodide are cooled at different rates. The solution that cools faster produces smaller crystals.

Context

Students need to be aware that igneous rock forms when magma cools and forms crystals. They should know from examining rock samples

and / or photographs that igneous rock such as granite contains crystals and that different types of igneous rock contain crystals of different

sizes.

Teaching points

The link that the students should be encouraged to make is that the intrusive igneous rock (the granite) has cooled slowly from magma, and

the rhyolite lava (extrusive igneous rock) has cooled very quickly. This leads to a fuller explanation of the terms intrusive and extrusive – the

intrusive rock has cooled slowly, at depth, where the overlying rocks have had an insulating effect. The extrusive rock has cooled quickly on

the surface of the Earth, on land or on the ocean floor, and so crystals have little time to form and are therefore small. The time taken for

cooling has had a direct observable effect on the physical appearance of the rock.

It is important to point out to students that they are looking at an analogy or a model – granite forms by crystallisation from a melt rather

than from a saturated solution.

It is likely that the first tube (the one that cools at room temperature) will contain some undissolved lead iodide and students may object

that this experiment is not a fair test. In fact the undissolved solute may tend to promote crystallisation by acting as seed crystals. Students

could be encouraged to design (and, if time allows, carry out) a better experimental procedure in which they pour a little of the saturated

solution into each of two boiling-tubes, leaving all the undissolved solid in the original tube to be discarded.

Timing

The activity takes about half an hour including about 15 minutes waiting for the solutions to cool.

The activity

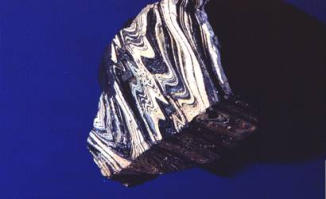

Ask the students to compare a sample of granite with a sample of rhyolite. Alternatively, they can look at photographs, such as Figure 1 and

Figure 2, if good samples are not available. Granite contains large crystals of the minerals feldspar, quartz and mica. The bulk of the rhyolite

contains no obvious crystals, when seen in hand specimen. Challenge the students to speculate on the reasons for the obvious difference in

crystal size.

Figure 1 A sample of granite, note the large crystals

Figure 2 A sample of rhyolite - the crystals are too small to see. (The colour banding was produced as the sticky lava flowed over the ground)

Students carry out the following activity. Half fill a boiling-tube with water. Add a small spatula measure of lead iodide. Heat over a Bunsen

flame, until the liquid starts to boil, taking care as the mixture can ‘bump’ very easily, spraying hot liquid out of the tube. Continue to boil for

a further minute, then quickly tip half of the contents into another clean boiling-tube. Cool this second tube and contents immediately

under a stream of cold water from the tap. Leave the original tube to cool down slowly.

Leave both boiling-tubes and contents for about 15 minutes, then inspect the contents. This allows the students some ‘writing up’ time. Both

tubes need to be at the same temperature before they are compared.

The yellow lead iodide powder gradually goes into solution on heating. On rapid cooling, lead iodide falls out of solution quickly, with tiny

sparkly flecks of crystals being formed. The solution that cools slowly produces distinctly larger crystals.

Apparatus

Each student or group will need

eye protection

2 boiling-tubes

boiling-tube rack

Bunsen burner

heatproof mat

boiling-tube holder

spatula

thermometer (0-100 °C)

Chemicals

a spatula measure of lead iodide (harmful by ingestion and inhalation of dust)

samples of granite and of rhyolite (or photographs, see Figures 1 and 2, if samples are not available) - suitable specimens can be obtained

from a geological supplier. Click here for details of some suppliers .

Safety notes

Wear eye protection.

Lead iodide is harmful.

It is the responsibility of the teacher to carry out an appropriate risk assessment.

Answers to questions

Q 1. The granite has the larger crystals.

Q 2. The crystals are larger in the tube that cooled more slowly, and smaller in the tube that cooled more quickly.

Q 3. The tube with the larger crystals cooled more slowly.

Q 4. Rhyolite cooled faster.

Q 5. Rock that cools underground (intrusive rock) will tend to cool more slowly than rock that cools on the surface (extrusive rock)

because of the insulating effect of the rocks above it. Other sensible suggestions should be given credit.

Extension

An alternative practical activity that may be used to illustrate the effect of rate of cooling on crystal size is to cool molten salol (phenyl 2-

hydroxybenzoate, phenyl salicylate) on microscope slides that are at different temperatures. (Safety note; salol presents a minimal hazard.)

In this experiment, salol is melted in a boiling-tube in a hot water bath. A few drops of the melt are placed, using a glass rod, onto two slides

– one that has been cooled in a freezer and one that has been warmed in a water bath (and then dried). Each sample should immediately be

covered by another slide at the same temperature. Once they have formed, the crystals can be observed using a hand lens, microscope or

on an OHP, projection microscope or video microscope. The crystals that form on the cooled slide should be smaller than those on the

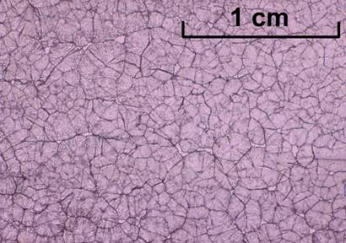

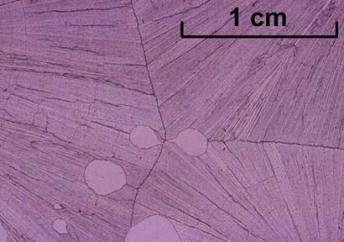

warmed slide, see Figures 3 and 4.

This activity is a better analogy with crystallisation of magma than the lead iodide experiment, because it involves crystallisation from a

melt. The activity is not, however, 100% reliable, partly because of supercooling of the salol which can delay crystallisation, and teachers

may wish to try it out several times before doing it with a class. Some suggested tips for success include:

Avoid overheating the salol – heat it only until it has just melted (42 °C).

Once the slides have been removed from the freezer and water bath respectively, speed is essential to ensure that there is a significant

difference in temperature between them once the salol is placed on them.

Use another slide at the same temperature to cover the salol on the slides – this makes the rate of cooling more uniform and prevents

crystals growing vertically upwards towards the observer thus appearing smaller in cross section than they actually are.

Figure 3 Small crystals of salol formed by rapid cooling

Figure 4 Large crystals of salol formed by slow cooling

Crystal size and cooling

rate: fast and slow

cooling of lead iodide:

teachers’ notes

Level

This activity is intended for students aged 11-14.

Topic

The activity relates to the process of igneous rock

formation by the cooling of magma. It can be used

to illustrate how the rate at which molten rock

cools affects the size of the crystals that form

within the solid rock – rapid cooling producing

small crystals, slower cooling producing larger

ones.

Description

Hot, saturated solutions of lead iodide are cooled

at different rates. The solution that cools faster

produces smaller crystals.

Context

Students need to be aware that igneous rock

forms when magma cools and forms crystals. They

should know from examining rock samples and / or

photographs that igneous rock such as granite

contains crystals and that different types of

igneous rock contain crystals of different sizes.

Teaching points

The link that the students should be encouraged to

make is that the intrusive igneous rock (the

granite) has cooled slowly from magma, and the

rhyolite lava (extrusive igneous rock) has cooled

very quickly. This leads to a fuller explanation of

the terms intrusive and extrusive – the intrusive

rock has cooled slowly, at depth, where the

overlying rocks have had an insulating effect. The

extrusive rock has cooled quickly on the surface of

the Earth, on land or on the ocean floor, and so

crystals have little time to form and are therefore

small. The time taken for cooling has had a direct

observable effect on the physical appearance of

the rock.

It is important to point out to students that they

are looking at an analogy or a model – granite

forms by crystallisation from a melt rather than

from a saturated solution.

It is likely that the first tube (the one that cools at

room temperature) will contain some undissolved

lead iodide and students may object that this

experiment is not a fair test. In fact the

undissolved solute may tend to promote

crystallisation by acting as seed crystals. Students

could be encouraged to design (and, if time allows,

carry out) a better experimental procedure in

which they pour a little of the saturated solution

into each of two boiling-tubes, leaving all the

undissolved solid in the original tube to be

discarded.

Timing

The activity takes about half an hour including

about 15 minutes waiting for the solutions to cool.

The activity

Ask the students to compare a sample of granite

with a sample of rhyolite. Alternatively, they can

look at photographs, such as Figure 1 and Figure 2,

if good samples are not available. Granite contains

large crystals of the minerals feldspar, quartz and

mica. The bulk of the rhyolite contains no obvious

crystals, when seen in hand specimen. Challenge

the students to speculate on the reasons for the

obvious difference in crystal size.

Figure 1 A sample of granite, note the large

crystals

Figure 2 A sample of rhyolite - the crystals are too

small to see. (The colour banding was produced as

the sticky lava flowed over the ground)

Students carry out the following activity. Half fill a

boiling-tube with water. Add a small spatula

measure of lead iodide. Heat over a Bunsen flame,

until the liquid starts to boil, taking care as the

mixture can ‘bump’ very easily, spraying hot liquid

out of the tube. Continue to boil for a further

minute, then quickly tip half of the contents into

another clean boiling-tube. Cool this second tube

and contents immediately under a stream of cold

water from the tap. Leave the original tube to cool

down slowly.

Leave both boiling-tubes and contents for about

15 minutes, then inspect the contents. This allows

the students some ‘writing up’ time. Both tubes

need to be at the same temperature before they

are compared.

The yellow lead iodide powder gradually goes into

solution on heating. On rapid cooling, lead iodide

falls out of solution quickly, with tiny sparkly flecks

of crystals being formed. The solution that cools

slowly produces distinctly larger crystals.

Apparatus

Each student or group will need

eye protection

2 boiling-tubes

boiling-tube rack

Bunsen burner

heatproof mat

boiling-tube holder

spatula

thermometer (0-100 °C)

Chemicals

a spatula measure of lead iodide (harmful by

ingestion and inhalation of dust)

samples of granite and of rhyolite (or

photographs, see Figures 1 and 2, if samples are

not available) - suitable specimens can be

obtained from a geological supplier. Click here for

details of some suppliers .

Safety notes

Wear eye protection.

Lead iodide is harmful.

It is the responsibility of the teacher to carry out

an appropriate risk assessment.

Answers to questions

Q 1. The granite has the larger crystals.

Q 2. The crystals are larger in the tube that

cooled more slowly, and smaller in the tube that

cooled more quickly.

Q 3. The tube with the larger crystals cooled

more slowly.

Q 4. Rhyolite cooled faster.

Q 5. Rock that cools underground (intrusive

rock) will tend to cool more slowly than rock that

cools on the surface (extrusive rock) because of

the insulating effect of the rocks above it. Other

sensible suggestions should be given credit.

Extension

An alternative practical activity that may be used

to illustrate the effect of rate of cooling on crystal

size is to cool molten salol (phenyl 2-

hydroxybenzoate, phenyl salicylate) on microscope

slides that are at different temperatures. (Safety

note; salol presents a minimal hazard.)

In this experiment, salol is melted in a boiling-tube

in a hot water bath. A few drops of the melt are

placed, using a glass rod, onto two slides – one

that has been cooled in a freezer and one that has

been warmed in a water bath (and then dried).

Each sample should immediately be covered by

another slide at the same temperature. Once they

have formed, the crystals can be observed using a

hand lens, microscope or on an OHP, projection

microscope or video microscope. The crystals that

form on the cooled slide should be smaller than

those on the warmed slide, see Figures 3 and 4.

This activity is a better analogy with crystallisation

of magma than the lead iodide experiment,

because it involves crystallisation from a melt. The

activity is not, however, 100% reliable, partly

because of supercooling of the salol which can

delay crystallisation, and teachers may wish to try

it out several times before doing it with a class.

Some suggested tips for success include:

Avoid overheating the salol – heat it only until it

has just melted (42 °C).

Once the slides have been removed from the

freezer and water bath respectively, speed is

essential to ensure that there is a significant

difference in temperature between them once the

salol is placed on them.

Use another slide at the same temperature to

cover the salol on the slides – this makes the rate

of cooling more uniform and prevents crystals

growing vertically upwards towards the observer

thus appearing smaller in cross section than they

actually are.

Figure 3 Small crystals of salol formed by rapid

cooling

Figure 4 Large crystals of salol formed by slow

cooling

teacher’s notes

student’s notes

- Home

- contents

- help

- glossary

- Magnetic patterns 1

- Magnetic patterns 2

- Mantle convection

- Metamorphics

- Minerals & elements

- Plate riding

- Plate tectonic story

- Protecting the earth

- Rock cycle in lab

- Sedimentary rocks

- Separating mixtures

- Sequencing of rocks

- Solid mantle

- Structure of earth 1

- Structure of earth 2

- Structure of earth 3

- Tree rings

- Weathering

- Gravestones

- Lab volcano

- Investigate earth